The Internal Revenue Service (IRS) maintenance regulations guide asset owners on costs to deduct or capitalize on for repairs and maintenance of their assets. The IRS permits businesses to deduct expenses they incur for maintenance that keeps a tangible asset in normal operating conditions.

Managers can subtract qualified annual deductions and recover capitalized costs for amortization, depletion, or depreciation. The regulations only apply to business owners, including landlords and their rental properties, but not to private homeowners.

What Are IRS Maintenance Regulations?

The IRS classifies “routine maintenance” as activities intended to keep assets efficiently operating under normal conditions. Routine maintenance keeps assets in good working condition but doesn’t prolong their lifespans or increase their value. For instance, changing the engine oil on a car is routine maintenance–it keeps the car operating normally without increasing its value. But replacing the car’s transmission would prolong its lifespan.

Changing the engine oil is a maintenance cost that a business can deduct, but the cost of replacing the transmission can be capitalized. Expenses that improve an asset, adapt it for a new use, or restore its normal condition typically depreciate over the years. The IRS refers to such expenses as betterments, restorations, or adaptations:

- Betterments: Maintenance activities that improve an asset. These include repairs that fix pre-purchase defects, defects that occurred during the asset production, enhance the asset’s capacity, or improve the asset’s productivity, quality, or efficiency.

- Restorations: Repairs intended to restore an asset to its normal operating condition. These include the replacement of a major component of the asset or reconstructing the asset to like-new condition. Maintenance activities that result in a deductible loss for the asset or its components also are classified as restorations.

- Adaptations: Expenses for maintenance activities that change the use of an asset. According to the IRS, what businesses pay to adapt an asset to a new use besides the original intended purpose is an adaptation expense. For example, converting a factory plant to a showroom is an example of an adaptation expense.

According to the IRS, businesses can capitalize on betterment, restoration, and adaptation costs. The final tangibles regulations guide organizations on the type of costs to capitalize or deduct per Section 162 of the Internal Revenue Code (IRC).

IRS Maintenance Regulations Resources

Organizations can deduct the amounts they pay for the maintenance and repairs of tangible assets if they don’t qualify for capitalization. However, they can choose to capitalize on the costs depending on their internal books and record-handling policies. Minor costs can be deducted immediately while major costs are depreciated over a period of time. Depreciation refers to the process of spreading asset costs over the lifespan.

The IRS issued the final repair regulations that guide the acquisition, production, or improvement of tangible assets. The regulations clarify the type of maintenance costs that businesses should deduct or capitalize. They also address how businesses should retire depreciable assets. These particular IRS maintenance regulations break down into five major areas:

- Reg. 1.162-3: cost deductions for materials and supplies

- Reg. 1.162-4: cost deductions for maintenance and repairs

- Reg. 1.263(a)-1: expenditures to capitalize

- Reg 1.263(a)-2: amount businesses deduct to acquire or produce tangible assets

- Reg 1.263(a)-3: amount paid to improve or enhance gt tangible assets

IRS Publication 535 of 2019 allows businesses to deduct the costs of removing a retired depreciable asset if installing a replacement asset.

Businesses also can incur costs for making their facilities easily accessible to the elderly and persons with disabilities. This includes installing elevators, ramps, and accessibility symbols. These costs can be deducted, but the IRS puts a limit on the amount of the deductions. They also must meet the requirements and guidelines outlined in the American Disabilities Act (ADA) of 1990.

Three Safe Harbor Rules

The final repair regulations introduced Safe Harbor rules that provide exceptions for writing off expenses. The rules allow businesses to deduct expenses under given circumstances even if they don’t meet all the requirements for a deduction. The Safe Harbor rules include:

- $5,000 De Minimis Safe Harbor: This rule allows businesses to deduct expenses for maintenance and repairs if the item or invoice costs no more than $2,500. However, businesses with applicable financial statements can make deductions up to $5,000.

- Safe Harbor for Small Projects: This applies to maintenance and repair costs that are $10,000 or less, and can be used for costs that are 2 percent of the unadjusted basis of the property. The rule only applies to businesses with less than $10 million in revenue, and the unadjusted basis for the property is less than $1 million.

- Safe Harbor for Routine Maintenance: The rule allows businesses to deduct expenses for repairs that fall under routine maintenance. But the repairs should be recurring maintenance activities that are expected to be performed, resulting from wear and tear in the line of business, and necessary for efficient normal operation of the asset. The repairs also should be performed more than once every 10 years for buildings and similar structures or more than once within the lifespan of other asset types.

Expenses categorized as betterments don’t qualify for the routine maintenance Safe Harbor deductions.

Get MaintainX to Help Manage Regulations

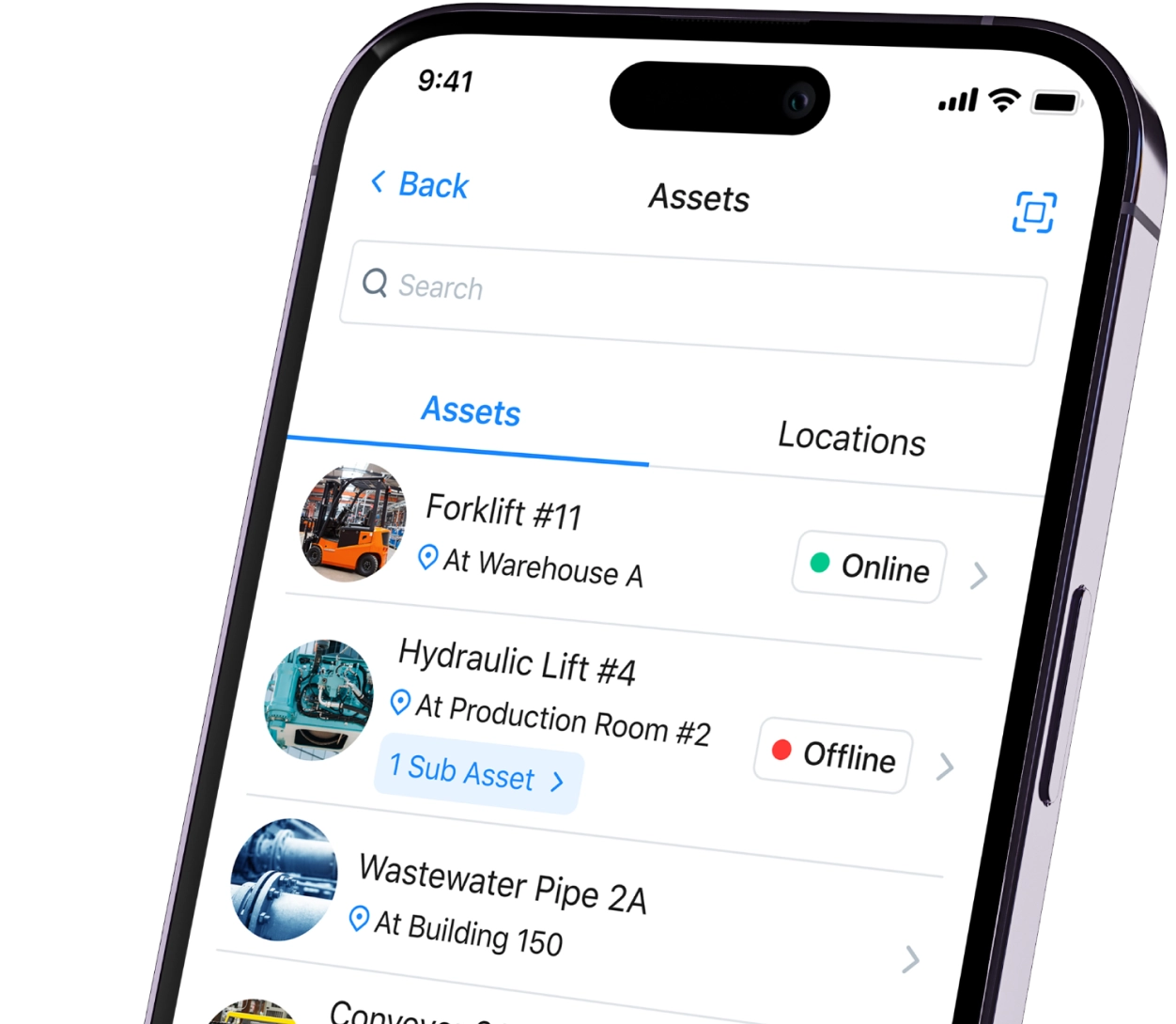

A well-planned maintenance strategy can help an organization keep its finances in order by tracking capital improvements and possible deductions. It enables detailed and timely communication by maintaining an inventory of goods and services when they’ll be needed and in what quantity. The maintenance department can provide the accounting department with proper records and documentation for tax purposes. Organizations can centralize their data using computerized maintenance management systems (CMMS) to eliminate redundant data entry and make it easier for finance teams to access maintenance data for tax purposes.

Caroline Eisner

Caroline Eisner is a writer and editor with experience across the profit and nonprofit sectors, government, education, and financial organizations. She has held leadership positions in K16 institutions and has led large-scale digital projects, interactive websites, and a business writing consultancy.

See MaintainX in action